10 Photographers That Have Inspired My 'Journey'

Nov 09, 2023

First published in February 2022, updated in November 2023

"Art is theft" - Pablo Picasso

It is a cliche, I know. But photography is a journey. And the route that it follows is influenced by many things. Not least of all the people we meet along the way.

It wasn't until I read Steal Like an Artist by Austin Kleon that I realised the extent artists are influenced by each other. Of course, we don't like the term 'steal'. We prefer to think of it as having been inspired. But what is the difference?

I suspect there isn't one. But if there were, might it be acknowledgement? To me, it feels wrong to use someone else's work without crediting them. So, when that work has been a source of inspiration, we should probably be upfront about that too.

In this article, I want to acknowledge 10 photographers that have inspired my photography in some way.

David Noton

In 2006, when I first became interested in photography, I was an avid reader of Practical Photography (YouTube was still in its infancy back then). David Noton was a regular contributor and I recall a story of one visit to Tuscany. My memory is a little hazy, and I may have some of the details wrong, but it went along the lines of...

Each morning he rose before sunrise and made his way to a vantage point that he had scouted on an earlier trip. He had a vision in his mind of the photograph that he wanted to create, but each morning the necessary conditions failed to materialize and he would return to wherever he was staying empty-handed. Then, on the final morning, at the last opportunity, the planets aligned and he got the shot.

I remember thinking at the time that this level of commitment was beyond me. All that effort for a single photograph? It seemed to be such little reward for such a lot of work. But that one anecdote has taught me so much about what it takes to produce our best photos. We don't just need a clear vision of what we want to create, but also the self-belief, commitment and determination to see that vision through to the end.

Five years in the making - David Noton helped me to understand the extremes we sometimes have to go to produce our best work.

Michael Kenna

The first photographer to influence my photography directly was Michael Kenna. I stumbled across his work purely by chance. It was unlike anything that I had encountered before.

I tried my hardest to understand what I found so compelling about his photographs. I was drawn to his use of strong subjects and simple compositions, devoid of any form of distraction. I realise now that this is a crude oversimplification, but it was to become the foundation that I would build my own style upon.

Today, my most common failing is to forget this. To try to include too many competing elements in the frame. Every now and then I take a fresh look at Micheal's work and remind myself of this most important of lessons.

Micheal Kenna's influence is obvious in many of my best photographs.

Ansel Adams

I doubt there is a landscape photographer working today that hasn't been influenced in some way by Ansel Adams. If not directly, then it seems almost impossible that they haven't been touched by someone who was in turn inspired by the great man.

In that respect, Ansel has probably been a bigger influence on my work than I will ever know. But it is one of his most famous quotes, that challenges the expectations that we place upon ourselves, that has had the biggest impact on me.

"12 significant photos in any one year is a good crop."

I, like many photographers I am sure, used to pile a huge amount of pressure on myself to produce a 'good' image every time I went out with my camera. Of course, I returned home frustrated more times than not. But if the greatest landscape photographer of all time set such seeming modest targets for himself, why was I setting my own bar so much higher?

This realisation didn't just stop the frustration, it set me free! Today, my hit ratio is about 10%. 1 in 10 trips result in a photo worthy of my portfolio. The rest of the time I produce images that range from 'just missing the mark' to 'down-right awful'. But that is OK, because every photograph is an opportunity to learn and I learn more from every bad image than I do from the good ones.

For the past 3 years, I have consistently produced between 10 and 15 portfolio quality images per year. The rest is mostly a lot of dross. To my critics, these only prove that I am a poor photographer. "A good photographer should be able to produce good photographs no matter what the conditions". But as I have stopped placing such unrealistic expectations on myself, I am not about to allow others to do the same.

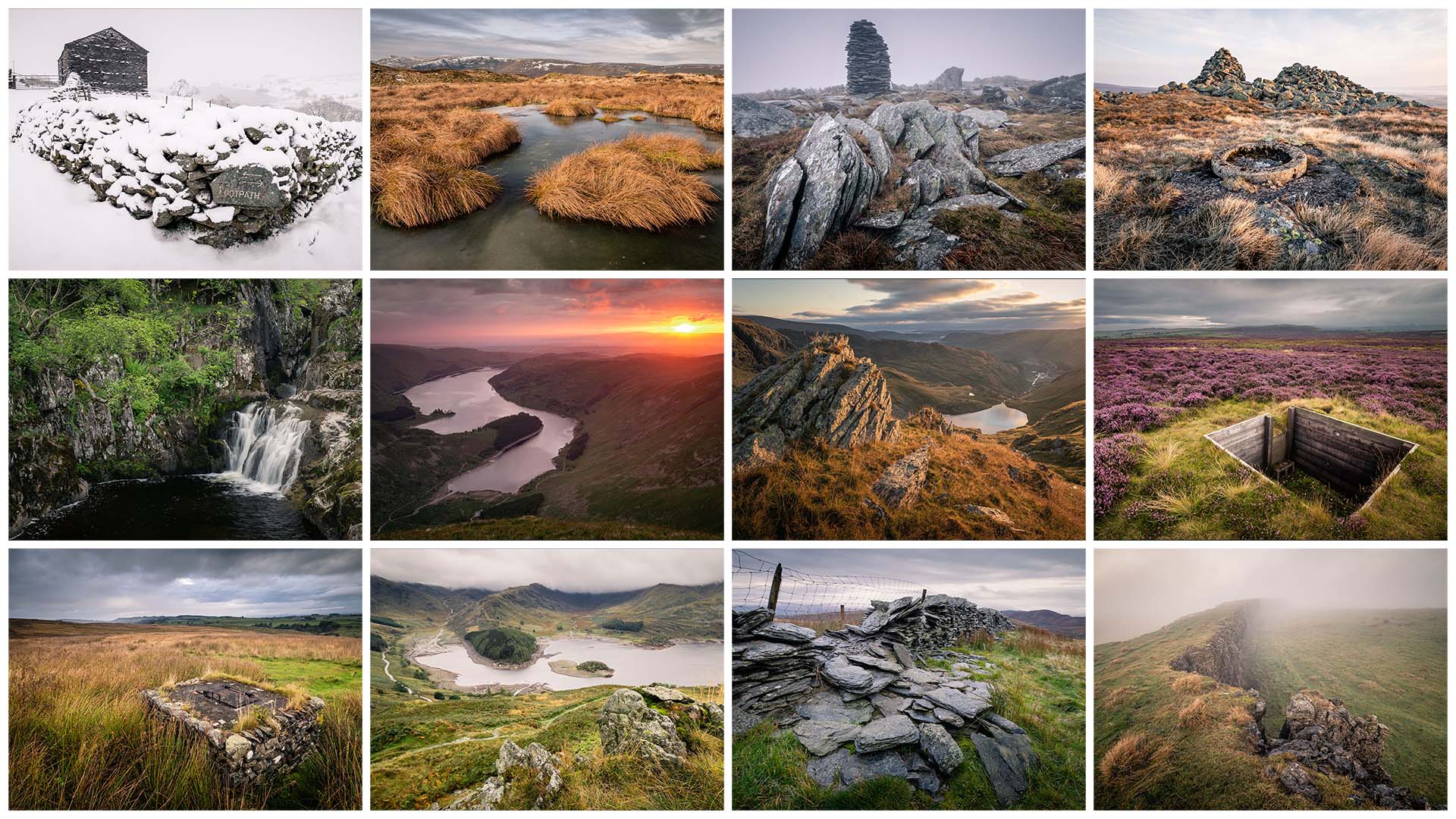

Only 1 in 10 trips result in an image worthy of my portfolio.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Not all of the photographers that have inspired me are landscape photographers. I have for a long time been a fan of the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, best known as a pioneering street photographer.

What appeals most to me about his work is his impeccable timing, never more evident than in his 1932 masterpiece, Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare. In 1952 he published the book The Decisive Moment in which he is quoted as saying...

"To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organisation of the forms which give that event its proper expression."

I learnt from Cartier-Bresson that knowing when to press the shutter button is just as important as knowing what to point the camera at in the first place. Of course, as a landscape photographer in the modern age, this decision is often deferred till afterwards, when in the digital darkroom. But the principle is just as relevant today as it has always been.

Cartier-Bresson spoke of the decisive moment; a split second in time perfectly frozen for eternity.

Robert Capa

Robert Capa was best known as a fearless war photographer who along with Henri Cartier-Bresson, was one of the founder members of the Magnum Photo Agency. He is famously quoted as having said...

"If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough."

I suspect that Capa was being very literal, encouraging us to get up close and personal with our subjects. But I have taken his advice in a much more spiritual and emotional sense.

I am known almost exclusively for photographing the Lake District. Capa's words have inspired me to learn more about the history and culture of the area. And I am utterly convinced that having a greater appreciation for our subject can help us to form a greater emotional connection, producing better photographs as a result.

Researching the history of the Haweswater Reservoir helped me to understand the impact its construction had on the surrounding area.

Charlie Waite

Back in the days when I had a proper job, photography for me was an escape. I found it very hard to switch off, and work was never far from my thoughts. The only way I found to clear my mind was to get outside with my camera. Photography demanded so much focus that I could think of nothing else.

Photography for me became about relaxation, a form of mediation, and this started to show in my photographs. My best work reflected a feeling of calm and tranquillity. Colourful sunrises started to lose their appeal and I began to favour a more subtle colour palette. Bright, overcast mornings became my favourite for photography. But with my social media feed full of vivid skies and dramatic light, I found myself questioning this approach.

One day, while I was scrolling through Twitter, I came across a video by Charlie Waite in which he was discussing his photograph of Rydal Boathouse. In the video, Charlie challenged the notion that a landscape photograph needs direct light.

This struck a chord with me. So, I spent some time researching Charlie's work more deeply. To my delight, I found example after example of muted colours being used to great effect. If it was good enough for Charlie Waite, it was good enough for me!

Finding similarities that my work shared with one of the world's most highly respected landscape photographers was so affirming. It is impossible to overestimate the boost that this gave to my confidence, not just regarding my use of light and colour but for my approach in general.

Studying Charlie Waite's work gave me the confidence to continue to work with diffused light and a more muted colour palette.

Joe Cornish

I regularly review my images, looking for things that I do well as well as those that I need to work on. During one of those sessions, it became obvious to me that my compositions needed improving. I was aware of the basic aids, the rule of thirds, leading lines, etc. But something was missing, and I couldn't figure out what.

It is times like this when I turn to my bookshelf. And so I pulled a couple of my favourite books and began leafing through them. Amongst them was Masters of Landscape Photography, which features some of the finest landscape photographers working today.

Listed as the Master of Balance was Joe Cornish. Joe is someone that I have looked up to for many years and it reminded me of a quote from a book that co-wrote called Developing Vision and Style.

"I would hope my style reflects my belief in the interconnectedness of things, and a fascination of depth, and space, and texture, and light; and an overriding belief that composition (like life) is a question of balance."

Inspired by Joe, balance became my primary focus. And my compositions began to show considerable improvement. Today balance is one of the three primary aesthetics that I value most highly alongside order and depth.

Inspired by Joe Cornish, balance is one of the aesthetic qualities that I prize most highly.

Larry Burrows

Henry Frank Leslie Burrows, better known as Larry, was a photojournalist best known for his work during the Vietnam conflict. He is the author of One Ride on Yankee Papa 13, which tells the story of a fateful mission aboard a US Marine Helicopter. It is widely regarded as the best photo essay of all time and one of the most important photographic documents to emerge from the war in Vietnam.

From the moment that I read the story of YP13 I was hooked on the concept of the photo essay. What appeals most is how multiple photos can be combined to tell a more compelling story. The whole is, after all, greater than the sum of its parts.

Burrows has inspired me to create photo essays of my own, usually to tell the story of a location. I find story-telling in landscape photography to be extremely difficult. But if you can't tell a story with one image, try 2 or 3.

Larry Burrows inspired me to use multiple images to tell the story of the area around the village where I live.

Hans Stand

We all have our weaknesses. In a field such as photography, I have always believed that it is important to specialise. To become really good at one thing. Then, once that has been mastered, to shift focus to areas where improvement can be made.

When I first started to photograph the Lake District, I concentrated on capturing images from the edges of the lake and reservoirs. Once I had developed a degree of competency, I looked for a fresh challenge by heading up into the fells.

Despite growing up in the Chiltern Hills, surrounded by beech woodland, I have always struggled to find compositions in the woods. Each time I have tried to address this shortcoming, my research lead me to example after example where the photographer has used mist to create separation between foreground and background.

With only a few notable exceptions, most of my images use perspective to create a sense of depth. For that reason, I was always a little wary of relying on mist in my woodland photographs. I felt that if I was to retain some degree of authenticity, my woodland photographs should align with the rest of my portfolio.

For me, in the genre of woodland photography, the work of Hans Strand stands out from the crowd. While he is not averse to using mist, many of his woodland photographs also have the depth that I was looking for. As I studied his photos more closely, I began to appreciate the care taken when positioning the major lines in the frame. So this was were I decided to focus my attention. It was a revelation!

Hans Strand showed me that it was possible to produce woodland photographs that also had depth.

David Ward

The key to great landscape photography often comes down to the photographer's ability to match the subject to the conditions. I am fond of saying "there is not such thing as bad light, only the wrong subject". One of the mistakes that I make all the time is forcing a shot when conditions are not suitable. Most commonly, big vistas in flat light!

My typical response is simply to return when conditions are more suitable. However, as someone who works regularly with visitors to the Lake District, I am also aware that not everyone can 'come back tomorrow'. In an effort to help my clients maximise their time on location, I started to look for subjects that are less dependent on having great light. It was David Ward that supplied me with the answer...

"Shooting intimate landscapes increases both the amount of useable light and the number of available subjects."

Whilst my motives for considering more intimate compositions may have been commercial, I have thoroughly enjoyed the challenge and been surprised by the results. Not only does shooting intimate landscapes allow me to make better use of the available light they also provide a greater opportunity for creative expression.

David Ward has inspired me to turn to intimate compositions when the light does not favour the big vistas.